Sometimes I like to pretend I read books.

I might even write an essay about it!

You should check out my mixtapes man they're actually really sick I swear.

Sometimes I like to pretend I read books.

I might even write an essay about it!

|

by John G. Neihardt, 2014 (1932).

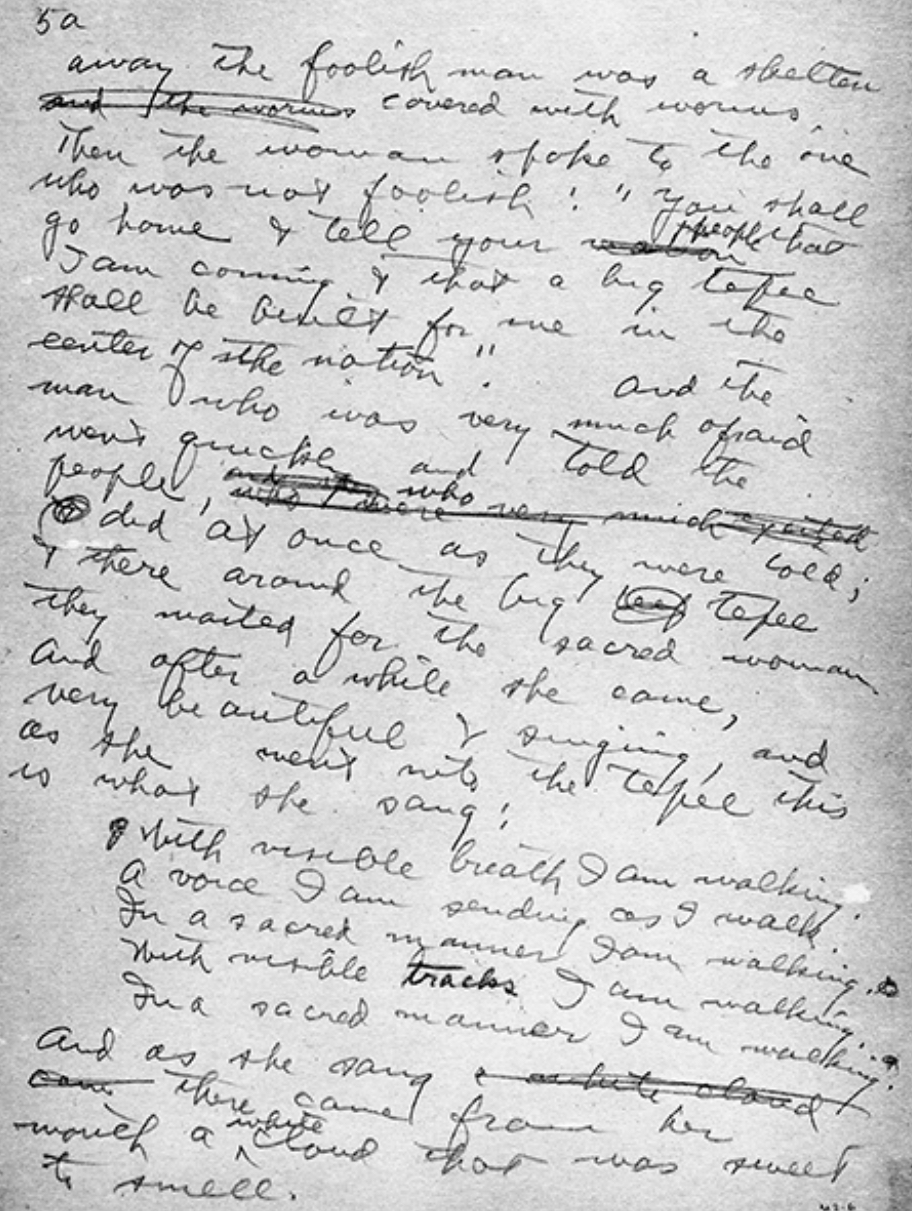

Finally got to tick off Black Elk Speaks (originally published in 1932) from my reading list, and it was better than I expected! Definitely a worthwhile read for those interested in Native American history and religion, and should be required reading for those living in Great Plains territory – though I can already hear the objections to this, that BES was still written by a white man and that there are plenty of better, more authentic resources out there (which I’d agree with! Joseph M. Marshall III’s The Journey of Crazy Horse should also be required reading). That’s one of the more interesting conversations to stem from the publishing of this book in 1932. Technically, this isn’t Black Elk speaking at all, as it’s all been filtered through the voice of Illinois-born, Missouri-based Anglo American scholar John G. Neihardt. He spent multiple years visiting with Black Elk and his friends regularly (shoutout Standing Bear), discussing for hours on end Black Elk’s life, his experiences from childhood to his witnessing of Wounded Knee, and most importantly, the meaning and significance of the Great Vision he witnessed at nine years old, sending him on the path of the medicine man. But Black Elk spoke Lakota, meaning his son Ben had to translate for him, while Neihardt’s daughter Hilda took a frankly insane amount of shorthand notes.  Sample of original translation notes from Neidhart's manuscript draft.

Sample of original translation notes from Neidhart's manuscript draft.

Using these notes, Neihardt transmuted Black Elk’s story into a brand new entity of its own, (almost) seamlessly combining Black Elk’s original words with the history, translations, elaborations, and academic-style poetry that Neihardt felt was necessary to appeal to a wider (mostly white) audience. But here arises the problem, highlighted by many critical Indigenous scholars throughout the 60s and onwards, after a boom in “new age” spiritualism amongst youngsters pretty much guaranteed BES’s status as a “standard text in the canon of American dissident spirituality” (from Ann Neumann). Essentially, this book cannot be Black Elk’s – the best it can amount to is a good-hearted revisionist account of an old medicine man’s experience of the last few years of the old life, painting Black Elk as a tragic aging prophet and the story of the Sioux people as a weakening shout on a fast-track towards vanishing completely. |